The Beginning of the Jacksonville Beach American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps and Station #1

This article was written by Beaches Museum Archives & Collections Manager, Sarah Jackson.

Though Pablo Beach only became an incorporated city in 1907, the community was already well on its way to becoming a popular beach destination on the Floridian coast of the Atlantic Ocean. Before 1912, however, residents and visitors to Pablo Beach, now known as Jacksonville Beach, swam in the ocean waters at their own risk. Over the years accidents occurred with inexperienced bathers, and even experienced bathers, caught in rip currents and other dangerous situations in or near the water. There were no trained officials at the beach to help bathers in distress and the closest medical facilities were miles away in Jacksonville.

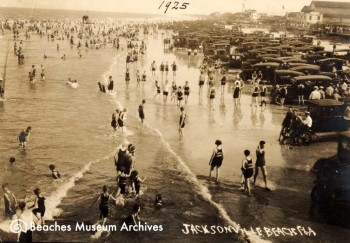

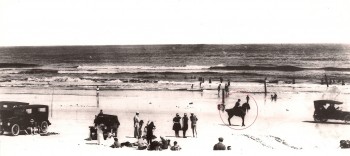

This photo shows the Jacksonville Beach beachfront filled with crowds of bathers and cars in 1925.

The United States Volunteer Life Saving Corps of Pablo Beach was founded in 1912 by Clarence H. McDonald and Dr. Lyman G. Haskell. McDonald was appointed supervisor of public recreation for Jacksonville by the city government that year. Shortly after he took up his new position, a young nurse drowned in Pablo Beach, which brought the lack of beach lifeguards and first aid to McDonald’s attention and set him on the path creating the Corps. As he began efforts to start a life saving organization, he met Dr. Haskell, the Physical Director of the Y. M. C. A. in Jacksonville at the time who had also recognized the great need for such a group and joined McDonald’s efforts. Haskell created swimming and gymnastics classes in 1912 which became the basis for future Corps training, and many of his students from these classes became the first members of the U. S. Volunteer Life Saving Corps.

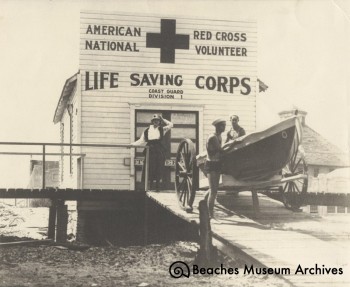

The first building for Station #1, ca. 1913.

The Corps officially opened its first station, funded by the city, on April 6, 1913. This first station was a wooden structure just large enough to house one or two boats, some equipment, and a handful of men. The small building quickly became insufficient to fulfill the needs of the volunteer lifeguards, but continued to serve as their station for several years.

Less than two years after its inception, the Corps experienced a significant change. Due to the efforts of Commodore Wilbert E. Longfellow, the American Red Cross began its water safety program in 1914, and the U. S. Volunteer Life Saving Corps was chartered on April 17 of that year to become the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps, Coast Guard Division #1. The small Pablo Beach station became known as Station #1.

The first building for Station #1 as it looked after 1914. The name of the front of the station was changed to reflect the group’s new identity as the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps, Coast Guard Division #1.

The first building, however, was prone to storm damage, even blowing over a couple of times during significant storms in its earliest years before being fixed to a concrete foundation around 1915. While the Corps made frequent repairs over the years, it was ultimately replaced in 1920. Made of concrete block, the second Station #1 housed first-aid rooms, a guard room, locker room, captain’s room, club room, and a dormitory. A few years later, a boat room and a second dormitory were added. This station weathered several hurricanes and served the Corps for almost 25 years.

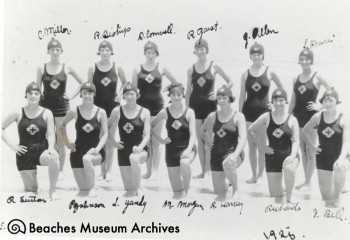

In its early years, the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps had a contingent of women guards. Formed in the late 1920s, they served the beach community for about a decade. Since the mid-1990s, women have been actively recruited to serve alongside their male colleagues as one unified corps.

In its early years, the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps had a contingent of women guards. Formed in the late 1920s, they served the beach community for about a decade. Since the mid-1990s, women have been actively recruited to serve alongside their male colleagues as one unified corps.

Talks began as early as the late 1930s to either remodel the station or replace the structure entirely. The second station was eventually torn down in December of 1945 and construction began on today’s Station #1 in 1946. Initially, the new station was expected to be built and operational in 1946, but due to problems with financing and materials needed for construction which were in short supply as WWII had only recently ended, construction was delayed for several months. Lifeguards and new recruits operated out of an old army hut on the beachfront throughout construction.

Full operations in the third Station #1 building began in 1948 with several improvements including a new observation tower known as the Peg. The older version of the Peg, similar to the mast and crow’s nest of an old ship, was replaced by a five-story tower connected to the main building. Constructed with the Art Deco style of architecture, the layout of this station is similar in many ways to the one it replaced.

The second building for Station #1, ca. 1940.

The American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps remains an iconic and crucial component of Jacksonville Beach and the surrounding area. Station #1 was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1914 and remains a focal point of Jacksonville Beach to the present day. The distinctive suits and red chairs that pepper the beaches throughout the summer months have remained unchanged for years. The organization continues to provide valuable services to the community including first aid and water safety education.

**The Volunteer Life Saving Corp, Inc. (VLSC) was established as a separate corporation in 2015.

Local lifeguards participating in the annual Meninak Ocean Marathon Swim around 1948 at the newly constructed third incarnation of Station #1. Photo by Virgil Deane.

Jacksonville Beach lifeguards on duty just north of the old pier, ca. 1926.

Lifeguards demonstrating drills to spectators in front of Station #1 in Jacksonville Beach in the 1920s.

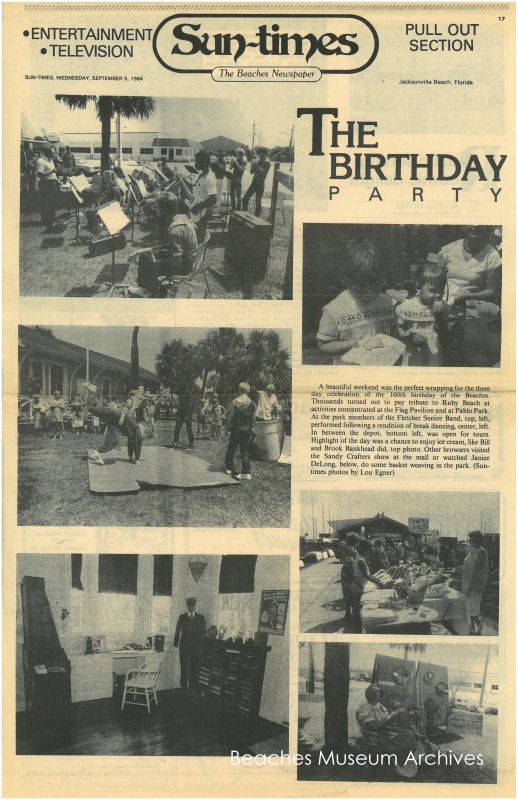

In 1984, the Beaches Area Historical Society hosted a series of events recognizing the centennial of Jacksonville Beach. Founded in 1884 by the Scull family, Jacksonville Beach was first known as Ruby Beach. William E. and Eleanor Scull were the first family to settle the area, working a post office and general store while living in tents on the beach with their two children, Ruby and Bessie. What began as a small, nearly unpopulated, nineteenth-century outpost on the route between Mayport and St. Augustine eventually grew into the thriving and lively Jacksonville Beach that Jean McCormick and the Beaches Area Historical Society wanted to commemorate with a centennial celebration in 1984.

In 1984, the Beaches Area Historical Society hosted a series of events recognizing the centennial of Jacksonville Beach. Founded in 1884 by the Scull family, Jacksonville Beach was first known as Ruby Beach. William E. and Eleanor Scull were the first family to settle the area, working a post office and general store while living in tents on the beach with their two children, Ruby and Bessie. What began as a small, nearly unpopulated, nineteenth-century outpost on the route between Mayport and St. Augustine eventually grew into the thriving and lively Jacksonville Beach that Jean McCormick and the Beaches Area Historical Society wanted to commemorate with a centennial celebration in 1984.  The celebration kicked off in 1983 when Florida Governor Bob Graham signed a proclamation designating 1984 as “Jacksonville Beaches Area Centennial Year.” From there, the Historical Society – led by Jean McCormick – spearheaded plans to ensure that the centennial celebration of Jacksonville Beach would be a year full of activity and events.

The celebration kicked off in 1983 when Florida Governor Bob Graham signed a proclamation designating 1984 as “Jacksonville Beaches Area Centennial Year.” From there, the Historical Society – led by Jean McCormick – spearheaded plans to ensure that the centennial celebration of Jacksonville Beach would be a year full of activity and events.

apping up its 40th year by rolling out a new name and logo. Started in 1978 as the Beaches Area Historical Society, the organization has been a staple in the community with the mission “to preserve and share the distinct history and culture of the Beaches area”.

apping up its 40th year by rolling out a new name and logo. Started in 1978 as the Beaches Area Historical Society, the organization has been a staple in the community with the mission “to preserve and share the distinct history and culture of the Beaches area”. After planes were used during the Great War for air-to-air combat, surveillance, and mail carriers, many U.S. pilots began using their skills to push the limits of aviation technology. Some modified their aircrafts to perform in stunt shows. Others, like Charles Lindberg seized the opportunity to create distance and time records. However, he was neither the only pilot nor the first to make a mark in the aeronautical history books. Jacksonville Beach played host to one famous record breaking pilot, Lt. James H. Doolittle, who set a new transcontinental flight record in 1922.

After planes were used during the Great War for air-to-air combat, surveillance, and mail carriers, many U.S. pilots began using their skills to push the limits of aviation technology. Some modified their aircrafts to perform in stunt shows. Others, like Charles Lindberg seized the opportunity to create distance and time records. However, he was neither the only pilot nor the first to make a mark in the aeronautical history books. Jacksonville Beach played host to one famous record breaking pilot, Lt. James H. Doolittle, who set a new transcontinental flight record in 1922. miles per hour and stayed at an altitude of 3,500 feet.

miles per hour and stayed at an altitude of 3,500 feet. n 22 hours and 27 minutes.

n 22 hours and 27 minutes.

word of mouth, letters amongst friends, running newspaper articles, as well as networking with other historical preservation groups and city council members. Likewise, the Society became heavily involved in local community activities. The April Opening of the Beaches parade signaled an early turning point for the Society. With a massive community turnout, an unexpected explosion of a nearby buggy during the parade ignited community awareness of the Society. Mr. Charles Cook Howell, Jr. wrote in a small note to Mrs. McCormick stating, “a true Champion has started the society off with a bang! This certainly argues well for the future.”

word of mouth, letters amongst friends, running newspaper articles, as well as networking with other historical preservation groups and city council members. Likewise, the Society became heavily involved in local community activities. The April Opening of the Beaches parade signaled an early turning point for the Society. With a massive community turnout, an unexpected explosion of a nearby buggy during the parade ignited community awareness of the Society. Mr. Charles Cook Howell, Jr. wrote in a small note to Mrs. McCormick stating, “a true Champion has started the society off with a bang! This certainly argues well for the future.” not stop them from putting one together. They utilized two small spaces in the Ocean State Bank and Beaches Guaranty Bank to display two exhibits “full of Memorabilia” that even included a 100,000 year old mammoth tooth.

not stop them from putting one together. They utilized two small spaces in the Ocean State Bank and Beaches Guaranty Bank to display two exhibits “full of Memorabilia” that even included a 100,000 year old mammoth tooth. appropriately named it Pablo Historical Park after Jacksonville Beach’s previous name. The park eventually became home to five “at risk” structures, items, memorials, and markers representing and celebrating the bygone era of the Beaches Area. However, the addition of the Beaches Museum and History Center in 2006 ushered a new phase of the Society’s role in the community.

appropriately named it Pablo Historical Park after Jacksonville Beach’s previous name. The park eventually became home to five “at risk” structures, items, memorials, and markers representing and celebrating the bygone era of the Beaches Area. However, the addition of the Beaches Museum and History Center in 2006 ushered a new phase of the Society’s role in the community. Jacksonville Beach. Located on Beach Blvd at the Beaches Museum & History Park, the garden, a Duval County Extension Demonstration Garden, is maintained by Master Gardener volunteers with the purpose of community education in gardening practices.

Jacksonville Beach. Located on Beach Blvd at the Beaches Museum & History Park, the garden, a Duval County Extension Demonstration Garden, is maintained by Master Gardener volunteers with the purpose of community education in gardening practices.

Orpah Jackson was, and continues to be, an important member of the Beaches community; working as a teacher for 55 years and actively participating in community projects. Born on June 15th, 1920 in Lumpkin, Georgia, her family later moved to a small neighborhood in East Mayport, Florida when she was 6 years old. This move was influenced by her mother’s desire to provide a better education for Orpah and her brother.

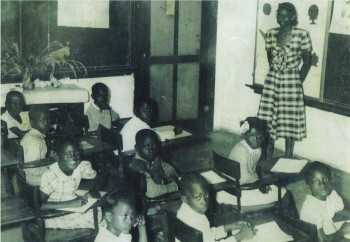

Orpah Jackson was, and continues to be, an important member of the Beaches community; working as a teacher for 55 years and actively participating in community projects. Born on June 15th, 1920 in Lumpkin, Georgia, her family later moved to a small neighborhood in East Mayport, Florida when she was 6 years old. This move was influenced by her mother’s desire to provide a better education for Orpah and her brother. In 1946 she moved back to Duval County and began a job as teacher and principal of 19 African American students in Mayport Village. When that school was closed in 1948, she began teaching 2nd grade at School #144 in Jacksonville Beach. Here, Orpah taught a wide range of subjects to her 2nd graders including reading, math, music, and physical education for 20 years.

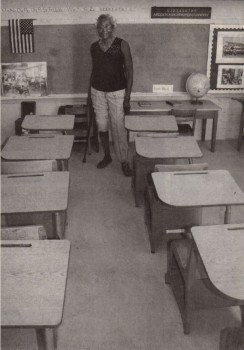

In 1946 she moved back to Duval County and began a job as teacher and principal of 19 African American students in Mayport Village. When that school was closed in 1948, she began teaching 2nd grade at School #144 in Jacksonville Beach. Here, Orpah taught a wide range of subjects to her 2nd graders including reading, math, music, and physical education for 20 years. Orpah was involved with many projects including the coordination of the integrated Vacation Bible School for the local churches, working with Meals on Wheels as a member of Church Women United, providing assistance to the neighborhood through the Donner Community Development Corporation, and serving as the first African American woman in Atlantic Beach to work on the voting Precinct. She currently serves as a member and Treasurer on the Board of the Rhoda L. Martin Cultural Heritage Center, which works to preserve the history of School #144 where her old classroom is on display.

Orpah was involved with many projects including the coordination of the integrated Vacation Bible School for the local churches, working with Meals on Wheels as a member of Church Women United, providing assistance to the neighborhood through the Donner Community Development Corporation, and serving as the first African American woman in Atlantic Beach to work on the voting Precinct. She currently serves as a member and Treasurer on the Board of the Rhoda L. Martin Cultural Heritage Center, which works to preserve the history of School #144 where her old classroom is on display.