A New Mission, Vision, and Values

The Beaches Museum & History Park’s Board of Directors started its 2017-2018 year strong with the presentation of its new Strategic Plan. The 10-month process was supported by the Community Foundation and was facilitated by Jana Ertrachter, the Ertrachter Group, who brought years of experience guiding organizations through the Strategic Planning Process.

The Beaches Museum & History Park’s Board of Directors started its 2017-2018 year strong with the presentation of its new Strategic Plan. The 10-month process was supported by the Community Foundation and was facilitated by Jana Ertrachter, the Ertrachter Group, who brought years of experience guiding organizations through the Strategic Planning Process.

A 12-member team comprised of board members, staff, volunteers and community members met monthly to gather and share information, derive key strategic issues and to assemble the roadmap for the Museum’s next three years.

Among other things, the group proposed new mission, vision and values statements that were unanimously adopted by the board at their October 10 meeting. The new mission statement of the Museum is “To preserve and share the distinct history and culture of the Beaches area”.

In addition to presenting the Strategic Plan, the new officers and two new members were announced. 2017-2018 officers will be: President-Jack Schmidt, Vice President-Linda Lanier, Treasurer-Randy Hayes and Secretary-Bill Carter. The board welcomed Chris Pilinko and Claudia Estes.

“We have a busy year of interesting programming, engaging special events and even more initiatives to share the fascinating history of our community” says Jack Schmidt, Board President. “Having the right board, volunteers and staff in place are key to making all of our endeavors a success and we look forward to a great year”.

Please visit Our Mission page to learn more about the Beaches Museum’s Vision, Values, and to review a complete copy of the Strategic Plan.

Admission to the Beaches Museum is free and information about programs and events can be found by calling 904-241-5657.

Rush Abry, a well-known Beaches photographer, managed to capture the only image of the crash site after wading through chest-high water to reach a tiny island where the patrol plane crashed and burned upon impact. His stunning black-and-white photo of four first-responders straddling the plane’s crumpled fuselage as a fire blazes behind them won a state press award for on-the-spot photography.

Rush Abry, a well-known Beaches photographer, managed to capture the only image of the crash site after wading through chest-high water to reach a tiny island where the patrol plane crashed and burned upon impact. His stunning black-and-white photo of four first-responders straddling the plane’s crumpled fuselage as a fire blazes behind them won a state press award for on-the-spot photography. The unique and memorable buildings of Atlantic Beach have greatly contributed to the character of this community throughout its life. The Continental Hotel – a monumental structure built at a time when there were almost no other buildings around – set the tone for the future of the community. The people who shaped Atlantic Beach in its early days hoped to form a more upscale community that drew in more elite residents. From converted carriage houses to a “hobbit house,” this trend has led to some of the most unique structures in the Beaches communities. The buildings mentioned below are just a few examples of the architecture found in Atlantic Beach throughout the years.

The unique and memorable buildings of Atlantic Beach have greatly contributed to the character of this community throughout its life. The Continental Hotel – a monumental structure built at a time when there were almost no other buildings around – set the tone for the future of the community. The people who shaped Atlantic Beach in its early days hoped to form a more upscale community that drew in more elite residents. From converted carriage houses to a “hobbit house,” this trend has led to some of the most unique structures in the Beaches communities. The buildings mentioned below are just a few examples of the architecture found in Atlantic Beach throughout the years. The Bull House. Built around 1902, this house represented some of the earliest construction in Atlantic Beach. The home of several members of the Bull family over the years, it was a longtime landmark in Atlantic Beach.

The Bull House. Built around 1902, this house represented some of the earliest construction in Atlantic Beach. The home of several members of the Bull family over the years, it was a longtime landmark in Atlantic Beach.

Abri. This Italian Renaissance Revival style house built around 1934 was originally owned by Broadway legend Lawrence Haynes. In his autobiography, “Joyous Life of a Singer”, Haynes attributes the name to a phrase used in World War I: “Vite a L’Abri,” which meant “Quick to the place where we are safe – where no harm can reach us.”

Abri. This Italian Renaissance Revival style house built around 1934 was originally owned by Broadway legend Lawrence Haynes. In his autobiography, “Joyous Life of a Singer”, Haynes attributes the name to a phrase used in World War I: “Vite a L’Abri,” which meant “Quick to the place where we are safe – where no harm can reach us.”

When discussing golf in the Beaches area, most will look towards Ponte Vedra Beach, particularly TPC Sawgrass and the annual PLAYERS Championship. However, Atlantic Beach has its own storied history in the world of golf.

When discussing golf in the Beaches area, most will look towards Ponte Vedra Beach, particularly TPC Sawgrass and the annual PLAYERS Championship. However, Atlantic Beach has its own storied history in the world of golf. The Selva Marina Country Club, a project initiated by Harcourt Bull, Jr., opened in 1958. Well received in the area, it featured a golf course designed by E. E. Smith and quickly grew to include tennis courts, a swimming pool, and a residential community. Selva Marina soon became an important and internationally recognized part of the community. It is best remembered as the birthplace of the Greater Jacksonville Open in 1965. Years later, this tournament became what is now known as the PLAYERS Championship. Playing host to many of golf’s greatest players including Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, Selva Marina created a name for itself in golf history. The Lady Jacksonville Open was also held at Selva Marina in 1975.

The Selva Marina Country Club, a project initiated by Harcourt Bull, Jr., opened in 1958. Well received in the area, it featured a golf course designed by E. E. Smith and quickly grew to include tennis courts, a swimming pool, and a residential community. Selva Marina soon became an important and internationally recognized part of the community. It is best remembered as the birthplace of the Greater Jacksonville Open in 1965. Years later, this tournament became what is now known as the PLAYERS Championship. Playing host to many of golf’s greatest players including Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, Selva Marina created a name for itself in golf history. The Lady Jacksonville Open was also held at Selva Marina in 1975. Today, the new Atlantic Beach Country Club continues Atlantic Beach’s golfing legacy at the site of old Selva Marina Country Club. In addition to the 6,815 square foot course redesigned by Erik Larsen, Atlantic Beach Country Club currently includes a neighborhood with 178 homesites, tennis courts, fitness facility, a junior Olympic swimming pool, and a 16,000 square foot clubhouse. Opened in January 2015, the revitalized 18-hole course was named as one of the nation’s Best New Courses by Golf Digest Magazine in 2014. The Web.com Tour Championship, part of the PGA TOUR, will be held at ABCC in Fall 2017.

Today, the new Atlantic Beach Country Club continues Atlantic Beach’s golfing legacy at the site of old Selva Marina Country Club. In addition to the 6,815 square foot course redesigned by Erik Larsen, Atlantic Beach Country Club currently includes a neighborhood with 178 homesites, tennis courts, fitness facility, a junior Olympic swimming pool, and a 16,000 square foot clubhouse. Opened in January 2015, the revitalized 18-hole course was named as one of the nation’s Best New Courses by Golf Digest Magazine in 2014. The Web.com Tour Championship, part of the PGA TOUR, will be held at ABCC in Fall 2017.

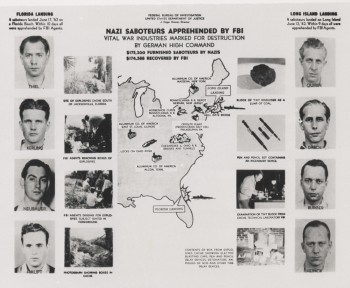

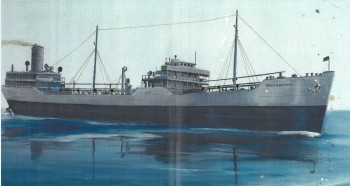

The night of April 10, 1942 started as a typical Friday night for people in the Beaches area. Jacksonville Beach was teeming with crowds kicking off their weekend with a visit to the boardwalk amusements, attending a dance at the pier, or catching the latest movie at the local theater. At approximately 10 p.m., however, the night took a very different turn.

The night of April 10, 1942 started as a typical Friday night for people in the Beaches area. Jacksonville Beach was teeming with crowds kicking off their weekend with a visit to the boardwalk amusements, attending a dance at the pier, or catching the latest movie at the local theater. At approximately 10 p.m., however, the night took a very different turn.

The Continental Hotel, constructed on the oceanfront in Atlantic Beach, opened in June of 1901. While it still featured luxury accommodations like Flagler’s other Florida resorts, it was simpler in design than hotels like the Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine. The hotel featured its own golf course, a detached veranda that wrapped around the hotel for lounging, an 800 foot ocean pier—the Atlantic Beach Pier—for fishing, picturesque drives around the area, and automobiling (racing) along the shore. Stretching along the oceanfront at 447 feet long and 47 feet wide, the wooden hotel provided a grand and palatial figure at the Atlantic Beach seashore. The building was yellow—a specific shade used by the FEC—with green shutters, accommodations for over 200 people, and a dining room that could seat 350 people. In advertisements for the hotel, the building was described as having an architectural design which was “perfectly balanced and pleasing to the eye” with its symmetry.

The Continental Hotel, constructed on the oceanfront in Atlantic Beach, opened in June of 1901. While it still featured luxury accommodations like Flagler’s other Florida resorts, it was simpler in design than hotels like the Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine. The hotel featured its own golf course, a detached veranda that wrapped around the hotel for lounging, an 800 foot ocean pier—the Atlantic Beach Pier—for fishing, picturesque drives around the area, and automobiling (racing) along the shore. Stretching along the oceanfront at 447 feet long and 47 feet wide, the wooden hotel provided a grand and palatial figure at the Atlantic Beach seashore. The building was yellow—a specific shade used by the FEC—with green shutters, accommodations for over 200 people, and a dining room that could seat 350 people. In advertisements for the hotel, the building was described as having an architectural design which was “perfectly balanced and pleasing to the eye” with its symmetry. Margaret McQueen was a lifelong advocate for residents of the Beaches community and the first African American elected to the Jacksonville Beach City Council. She was born February 5, 1940, in Jacksonville Beach, Florida. In 1958, McQueen moved to Indiana where she started a family and returned to the Beaches area in 1969. Newly divorced and the mother of four, McQueen enrolled at the University of North Florida and graduated in 1974 with a degree in education. As a mother and second grade teacher at Seabreeze Elementary School, McQueen saw the issues of drugs, crime, and poverty eroding the Beaches neighborhoods. In 1989, she lead the Jacksonville Beach Community Action Co-op to address community issues of crime and to further increase the cooperative partnership between citizens and police.

Margaret McQueen was a lifelong advocate for residents of the Beaches community and the first African American elected to the Jacksonville Beach City Council. She was born February 5, 1940, in Jacksonville Beach, Florida. In 1958, McQueen moved to Indiana where she started a family and returned to the Beaches area in 1969. Newly divorced and the mother of four, McQueen enrolled at the University of North Florida and graduated in 1974 with a degree in education. As a mother and second grade teacher at Seabreeze Elementary School, McQueen saw the issues of drugs, crime, and poverty eroding the Beaches neighborhoods. In 1989, she lead the Jacksonville Beach Community Action Co-op to address community issues of crime and to further increase the cooperative partnership between citizens and police. In 1991, at the age of 51, McQueen ran for the District 1 City Council seat. The election included the first ever district voting, which divided voters into geographic districts to choose their candidates. The District 1 City Council seat included the central and northeast sections of Jacksonville Beach, encompassing the same area where McQueen lived and raised her family. McQueen became the first African American elected to the Jacksonville Beach City Council on November 5, 1991, thus marking a historic moment for the Beaches community. She diligently served on the City Council from 1991 through 1994 and again in 1998. During that time, she saw the needs of the community improved. On June 29, 2013, McQueen passed away at the age of 73.

In 1991, at the age of 51, McQueen ran for the District 1 City Council seat. The election included the first ever district voting, which divided voters into geographic districts to choose their candidates. The District 1 City Council seat included the central and northeast sections of Jacksonville Beach, encompassing the same area where McQueen lived and raised her family. McQueen became the first African American elected to the Jacksonville Beach City Council on November 5, 1991, thus marking a historic moment for the Beaches community. She diligently served on the City Council from 1991 through 1994 and again in 1998. During that time, she saw the needs of the community improved. On June 29, 2013, McQueen passed away at the age of 73. The legacy of McQueen included the positive change one woman brought to her community through her efforts of grassroots organizing and civic engagement. She brought equal representation to her district and stood firm in her convictions for the belief in the greater good not just of her community, but for all the surrounding communities of the Beaches. She strove to make the Beaches a better place to live and spearheaded the volunteerism of both blacks and whites. The Beaches community is forever grateful for the contributions and leadership of women such as Margaret McQueen.

The legacy of McQueen included the positive change one woman brought to her community through her efforts of grassroots organizing and civic engagement. She brought equal representation to her district and stood firm in her convictions for the belief in the greater good not just of her community, but for all the surrounding communities of the Beaches. She strove to make the Beaches a better place to live and spearheaded the volunteerism of both blacks and whites. The Beaches community is forever grateful for the contributions and leadership of women such as Margaret McQueen.