Caught in the Crossfire

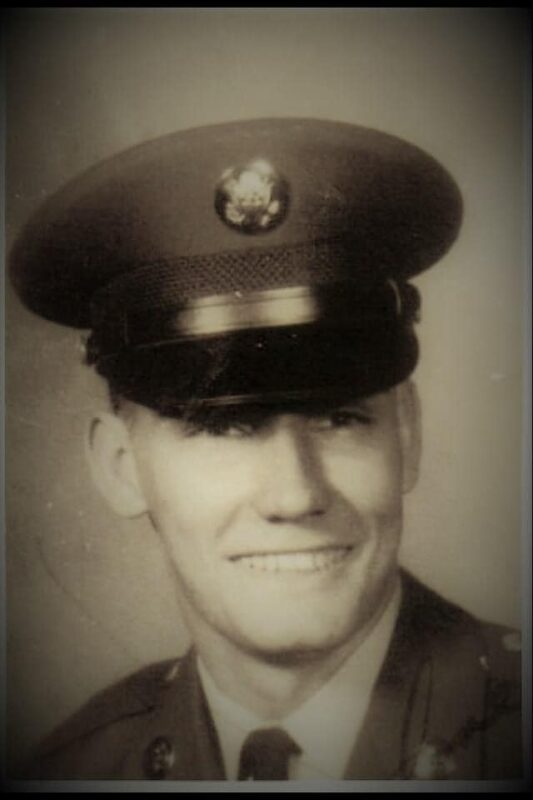

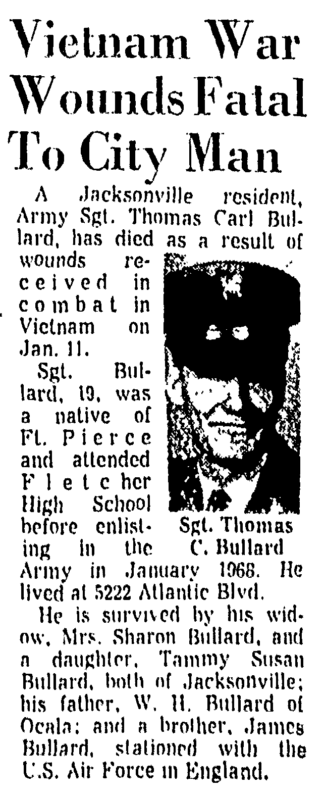

Bullard received the Bronze Star for valor in Vietnam.

By Johnny Woodhouse

Harold Fritz was in the lead command vehicle, an armored personnel carrier (APC) nicknamed by the South Vietnamese Army as the “green dragon,” when 2nd platoon’s seven-vehicle convoy stopped for refueling on Jan. 11, 1969.

Normally the executive officer of one of three scout platoons in Troop A, a unit of the U.S. Army’s 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, Fritz was taking the place of another platoon leader that dry Saturday morning.

During the refueling stop, the 24-year-old lieutenant had a chance to speak informally with his APC’s three-man enlisted crew, including topside gunners Charles Keith Day, 21, of Franklin, Ohio, and Thomas Carl Bullard, 19, of Jacksonville Beach, Florida.

Fritz’s orders were to move his mobile platoon to an overwatch position and provide an extra layer of security for the 1st platoon, which was escorting a resupply convoy traveling north on Highway 13, a road that stretched from Saigon to the border of Cambodia.

“The truck convoy went up that road twice a week,” recalled Fritz, now 81, in a phone interview in 2024. “There wasn’t a lot of action along the route, mainly sniper fire.”

Little did Fritz know, but not far from the refueling stop, a reenforced company of North Vietnamese Army soldiers was lying in wait for the 2nd platoon.

Beaches Roots

Two years earlier, Bullard attended Fletcher High School in Jacksonville Beach. He worked as a projectionist at the Royal Palm Theater in Atlantic Beach and enjoyed surfing near the Jacksonville Beach.

He and a friend, Glenn Folsom, a 1968 Fletcher graduate, rented a second-floor apartment at 823 16th Avenue South.

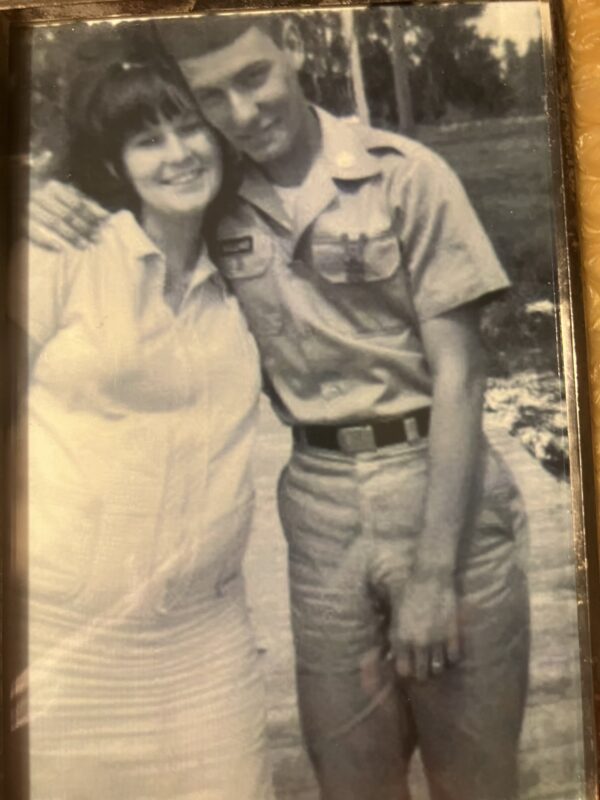

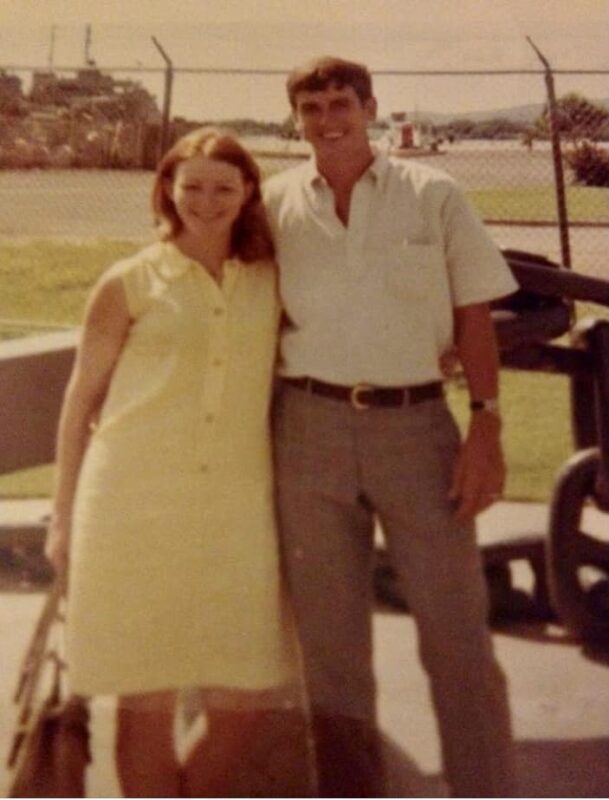

Bullard met Folsom when the pair attended Wolfson High in 1966. Folsom introduced Bullard to his sister, Sharon Folsom. After dating for a few months, the couple wed in November 1967.

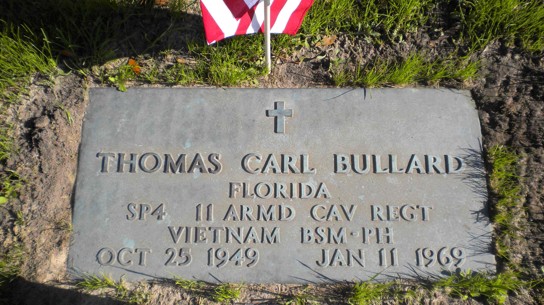

Four months later, and with a baby on the way, Bullard, then 18, followed his older brother, James Clifton Bullard, into the military. Their paternal grandfather, Joseph James Bullard Jr. (1894-1960), had served in combat during World War I, receiving the Purple Heart medal.

After graduating from basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, Bullard was assigned to the 11th Armored Calvary, based at Fort Meade, Virginia. He shipped out for Vietnam on June 13, 1968, and officially began his tour of duty on June 30. Before he left Jacksonville, Bullard and his wife posed for a photo outside her parent’s home near Memorial Hospital. Bullard’s wife gave birth to their daughter on June 19, 1968.

Specialized unit

Nicknamed the Blackhorse, the 11th was a specialized calvary unit equipped with light tanks and armored assault vehicles. In June 1968, the unit was under the command of Col. George S. Patton IV, son of the famous World War II tank commander.

Due to its widespread adaptability, the diesel-powered M113 armored personnel carrier became a ubiquitous symbol of the Vietnam War. It was equipped with a mounted 50-caliber machine gun and two mounted 60-caliber machine guns. But its aluminum hull was vulnerable to opposing machine gun fire and rocket grenades.

M-60 gunners like Bullard manned exposed positions atop the M113, making them easy targets from the waist up.

On that ill-fated Saturday in 1969, Bullard and Day, his fellow M-60 gunner, were at their usual positions near the rear of the lead command vehicle, crouching behind steel shields on either side of the troop compartment.

Like Bullard, Day, who was also married, began his tour of duty in June 1968. Both men held the same rank and military occupation specialty – armor reconnaissance specialist 4.

Caught in the crossfire

After speaking with Day and Bullard during the refueling stop, Fritz mounted the lead APC and took his seat below the cargo hatch, just behind the vehicle’s driver.

Both command vehicles had two radios, one to talk to the platoon and one to talk to company headquarters, Fritz said. “They also had twin radio antennas on top. The enemy looks for those,” he added.

While making its way to the overwatch position around 10:30 a.m., the platoon’s column of APCs, which was moving one behind the other, slowed down at one point to mark its position, Fritz said.

Then all hell broke loose. The NVA unit, which was set up in deep gullies that ran along both sides of the road, unleashed a barrage of crossfire toward Fritz’s lead command vehicle.

“The enemy was very close to us, maybe 5 to 10 feet away. Rocket grenades were whizzing all around and our radios were knocked out, so we couldn’t call for help,” said Fritz.

“We had no choice but to dismount. We were in the kill zone.”

When Fritz leaped to the ground from the top of his APC, he saw the limp bodies of both of his top-side gunners, who had been decimated by flanking fire. Fritz believes neither Day nor Bullard had even the slightest chance to return fire before they were killed.

“I pulled everyone in to create a protective barrier,” Fritz said. “The enemy tried to come over the top of us, but they found out we were tougher than they thought. We were determined to fight to the last man. That’s how dedicated we were.”

Despite being at a 5-to-1 disadvantage in manpower and running low on ammunition, Fritz’s platoon, which incurred heavy casualities, held off the ambushers with suppressing fire until a platoon of five M-48 tanks arrived to join the fight.

“We were covered in red dust and so was the enemy,” he recalled. “Vehicles were on fire and everyone was wounded.”

Despite being seriously wounded himself, Fritz refused to leave the battlefield until all his troopers were safely evacuated by helicopter. For his conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty, Fritz was the recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration.

A daughter’s lasting tribute

Along with the Purple Heart, both Day and Bullard were posthumously awarded the Bronze Star medal for valor.

Bullard’s remains were flown to Travis Air Force Base in California, and escorted to Jacksonville by his brother-in-law, Pfc. Robert Allen Jr.

He was buried in Jacksonville’s Greenlawn Cemetery with full military honors.

On Jan. 11, 2023, Bullard’s daughter, Tammy Pullen of Jacksonville, marked the 44th anniversary of her father’s passing in a Facebook post.

“I had the honor of meeting many of the brave men that served with and knew my father. I have great respect for each and every one of them,” the post said.

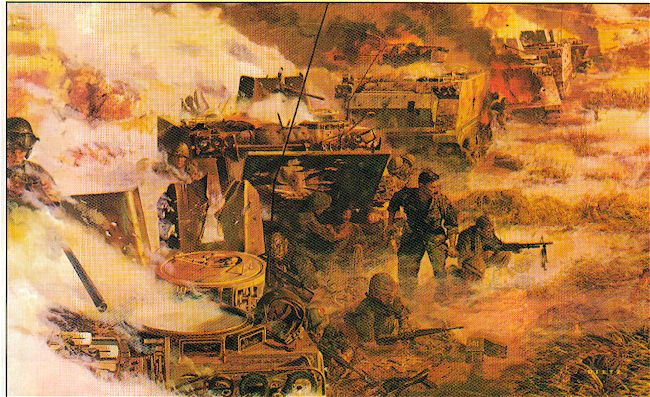

A year later, on Memorial Day 2024, Pullen posted: “Today, I think about the ultimate sacrifice my father, Thomas Bullard, and Charles Day made. An actual painting was commissioned of the battle they fought and died in. My dad was 19 when he died and I was 7 months old. I often wonder what our life would have been like if he lived. So proud of him and all the men and women who gave their lives defending freedom. Thank you.”